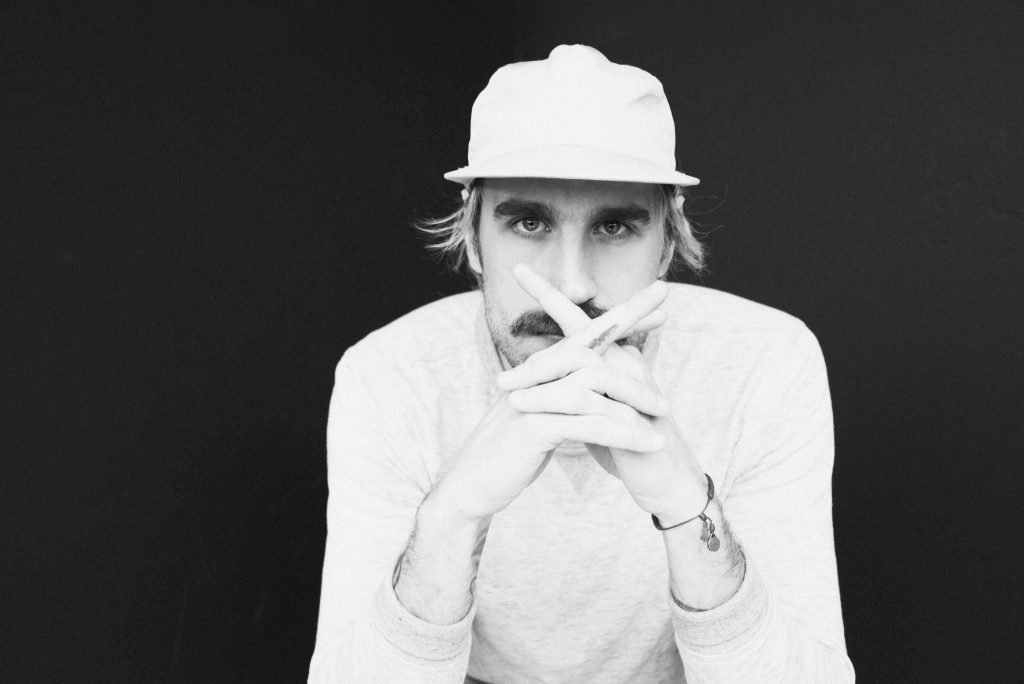

Interview: Rayland Baxter

Rayland Baxter, to borrow a phrase Bob Dylan borrowed from Walt Whitman, contains multitudes.

And, when it came time for Baxter to record his fourth album, If I Were a Butterfly, he set out to create a document of the complex, often conflicting components of his constitution.

“I wanted to make a free-feeling record that was completely who I am,” Baxter says. “I'm kind of hyperactive. I'm kind of beautiful inside. I'm kind of dark inside. I'm kind of lonely, and I'm a people person. I’m a deep thinker and a selfish rat and full of love all at the same time.”

For 18 months, the Nashville native decamped to the same refurbished rubber band factory on a 100-acre farm in Kentucky where he’d written and demoed songs for his prior release, Wide Awake. He immersed himself fully in the process of manifesting and recording If I Were a Butterfly at Thunder Sound Studios, where he claimed the producer’s chair for the first time. He slept in a barn, tinkered around the clock with instrumental ideas, and soaked up inspiration from his surroundings.

Equal parts daydream and fever dream, the collective fruits of this labor is a sonically dense self-portrait reminiscent of Michael Kiwanuka’s self-titled 2019 record. Home recordings from Baxter’s childhood; flute and synth flourishes; and reverb-ridden spoken word pieces thread its 11 amorphous tracks into a delightfully disorienting tapestry of sound.

If I Were a Butterfly sees Baxter spreading his wings as both a songwriter and imaginative curator. Members of Cage the Elephant and Alabama Shakes — as well as Baxter’s late father, Bucky Baxter, a premier pedal steel player who toured and recorded with Dylan and Steve Earle — brought his layered compositions to life in the studio along with his touring band. The album presents Baxter’s silver-lined reflections on love and loss against a moody, mysterious canvas of neo-soul, psychedelic folk-pop, frenzied glam-rock, and nostalgic piano balladry.

The sessions also simultaneously broke and bolstered him.

“That record was a 12-round fight, and I'm still concussed from it,” Baxter says. “But it's beautiful. This is the first interview I've done in a long time — and the first I've done since getting sober five months ago — and I'm noticing how I’m speaking so freely about it. I haven't listened to it in over a year. It's an emotional fucking fruit roll-up, man.”

Unlike most artists with his pedigree, Baxter didn’t grow up playing music. He played soccer as a kid in Nashville and, after moving with his mom and sister to Maryland in middle school several years after his parents divorced, he picked up lacrosse. He dove headfirst into the sport and ended up playing at Loyola University, but was kicked out his sophomore year after getting in a fight.

That’s when he first picked up a guitar with any true intention, encouraged and often accompanied by his dad. He started a cover band with friends to sharpen his playing and singing — and boost his confidence as a front man — eventually moving to Colorado to work as a snowboard instructor and, at night, make the rounds at open mics in Vail and Breckenridge. He released his debut album, Feathers & Fishhooks, in 2012, followed by Imaginary Man in 2015 and Wide Awake in 2018. An EP of Mac Miller covers dropped in 2019.

Asheville Stages spoke with Baxter on Halloween, a rare day off on a current tour that includes opening slots for Shakey Graves and headlining performances like his Saturday, Nov. 4, stop at The Orange Peel. He spoke, candidly and colorfully, about his creative journey and the wrenching yet rewarding experience of making If I Were a Butterfly while running music-related errands (picking up a guitar, getting his van repaired) around Music City.

Photo by Shervin Lainez

Jay Moye: You’re at the Ryman tomorrow night. Have you played there before, and did you grow up going to shows there?

Rayland Baxter: Yeah, we’re excited. I’ve played there a few times, actually. With Grace Potter, with Tedeschi Trucks [Band], and at a Bob Dylan festival, I think. I grew up in Nashville but don't remember going to the Ryman until I was like 25. But I did grow up going to Opryland and the Grand Ole Opry. There was a TV show filmed there called “Nashville Now,” which my dad played on quite a bit.

JM: I got to see your dad play a couple times. He was something else.

RB: Yeah, he was something else. What a gifted dude and musician.

JM: What was it like growing up with him as your dad?

RB: It was all I knew. He’d go out on tour for like six months with Steve Earle, and we’d pick him up at the airport with facial hair I didn't remember him having. When he played with Bob Dylan, I didn't really know anything about Dylan. I was in third grade, but I did know it was fucking cool. My parents divorced when I was three or four, so it was mainly vacations and holidays and stuff with him until I was out of college. When I moved to Nashville, he became a huge mentor to me in my young-adult life. He’d play every show with me, and we’d write songs together. His musicianship molded me and he gave me the best advice I still think about every day.

JM: What advice stands out?

RB: A lot of performing and songwriting advice. Like, “Make sure not to write too many songs in the minor key.” Or, “Stand up when you perform,” because I used to sit down all the time. He tried to instill some confidence in my stance and told me to look the audience in the eyes.

Beyond music, he taught me a lot about appreciating life and knowing what I can count on and what I shouldn't put my weight into or my bets on. Because of him, I appreciate the fog on the river, sunsets, and carpentry. I have the ability to listen to not only my inner self and the universe, but also to musicians I’m playing with. I know how to use musical terminology in the studio to get my point across. He was monumental in my life. I am who I am, in large part, because of him.

JM: He gave you your first guitar when you were in college?

RB: Well, we went on a motorcycle trip when I was in fifth grade, and he bought me a little shiny blue electric at a pawn shop. But I never played it. I went to stay with him over a Thanksgiving break and he gave me an acoustic guitar. I got suspended halfway through college and lived with him in Nashville for six months or so. He taught me some chords and little bits here and there on that guitar. I came into music with some encouragement from my dad, and once he saw that I was really into it, he was like, “OK, cool. I’ve got some advice for you.”

JM: Why is Thunder Sound Studios such a special good fit for you, creatively?

RB: It's within an hour from Nashville, but feels far away. One of my best friends, Billy Swayze, built that place up from the inside out from the remnants of an old rubber band company his family owned. He gave me a lot of advice on feeling — feeling music, feeling songs. I wrote 50 songs for Wide Awake in 2016, and those that ended up on the record are the ones where he’d poke his head in the room and say, “I like that one, Ray.” He passed in 2018 while he was still renovating the studio.

I moved back in December 2020 and spent a year and a half there — most of the time either with John Constable, the house engineer, or by myself. John taught me how to use Pro Tools and would leave me there for weeks at a time when he was in Nashville working. And I — and just so you know, I have no shame in saying this — ate food, drank booze, did drugs, and learned how to edit my record.

JM: How would you describe the look and feel of a rubber band factory?

RB: Rubber bands were made in the outer buildings, which are now just empty warehouses with boxes of old rubber bands that say, “What would Jesus do?” and rubber bands used for broccoli and other produce, all covered in dust. The factory relocated to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in the ‘90s, so it's pretty empty now. They used leftover rubber bands while building the studio; there's rubber bands in the walls and the soundproofed doors. And there are lots of spirits in those rooms.

JM: When you set out to make If I Were a Butterfly, did you have a specific vision?

RB: Before moving into the studio, I spent two months putting together 120 songs in the basement of the house I was living in at the time in East Nashville. Some full, some incomplete. I had them all in a notebook, and I went into the studio with different variations, different arrangements, and different band members there at any given time. Papers were spread out all over the floor. I had no rhyme or reason, which is the exact reason why I'm not producing my next record.

I learned a lot about myself during the making of that record. I pissed some people off and made some people smile. I pissed off myself, and I smiled in the completion of that record. It’s a timestamp, and an immersive experience when you listen to it. From the [home recordings of] childhood talking in the beginning, to the content of every song, to the sequencing of the record and the absolute amount of fucking work and energy that went into it. Some energy fueled by God and my father and his spirit, and some fueled by amphetamines, booze, and handfuls of mushrooms. And hawks flying around the building, and coyotes howling at night, and screech owls in the orchard behind in the studio.

And the really selfish way I was living when I made that record. I made friends and lost friends. I got in fights. I cried. I experienced absolute joy to the point of tears, facing the sunrise after staying up all night messing around in the studio. I went through everything with that record.

JM: For the listener, too. When you say you won't produce your next record, is that because of the mashup of emotions you just described or the tedium of playing the role of producer?

RB: There was nobody to push me along or cut me off when I was about to go on an eight hour dive into figuring out how to make a few sound effects happen. But I'm glad I did it, because now I know how to work with a producer for my next record. I can sit in the chair without having to frustratingly stand behind an engineer and ask, “Can you just move my vocal a little bit more towards the drumbeat?” Instead, I’ll say, “Do you mind if I get in there real quick and do some things I know will make the song better?” That's a big deal in the studio: either using your words to relay a request or an idea — which I'm not that great at — or using your own skill to dig into the tracks for a little bit and prepare them for the next round of assessment or recording.

JM: Your dad [who died in 2020] played pedal steel on the record?

RB: Yeah, on “Graffiti Street.” He came up in February; he’d drove overnight from Florida. He pulled up as I was sleeping in the guest house. It was pouring rain outside. I remember him saying, “Today's a great day to be in the studio!” And he killed it. He played on two other songs that didn't make the record, but hopefully we’ll get to put them out early next year. One’s called “Modern Man,” where he’s playing Jerry Garcia pedal steel.

JM: What’s it been like to play these songs — which you labored over so extensively and excruciatingly in the studio — live?

RB: It's been awesome. Some of them we’re not able to play because they're so complex and there's just four of us in the band. We play “Buckwheat,” “Billy Goat,” “Graffiti Street.” The last week of shows has been some of the best I've ever been a part of; the four of us are tight. We’ve got Kyle [Davis] on drums, Todd [Bolden], our bandleader on bass, and Barney [Cortez] on guitar. Those are the guys I made the record with. I'm just talking about them and they're walking up to the van right now.

JM: You mentioned the recordings of you as a [four-year-old boy] singing in the prelude to the album’s leadoff [and title] track. Much of the record feels nostalgic and semi-autobiographical. Was that intentional?

RB: Well, I'd written a lot of the lyrics before going into the studio. The childhood tapes were an afterthought as I was piecing the record together after a year-and-a-half of experimentation.

I've always looked back at my childhood with nostalgia. The older I get, the more I look back to see how I can learn from my childhood and rejoin with it to help me through tough times in my adult life. I love thinking about when I was a little kid wearing my Bahama shorts, riding around on my tricycle, and playing soccer in the field outside my school. I loved that time. It was so easy, man. The world was at war in a different way. But there was no fucking social media. There was no judgment from behind closed doors. There was none of this stuff a lot of us feel around us. I didn't have those feelings then. I really want to go back to those days all the time. That's what came out on the record.

IF YOU GO

Who: Rayland Baxter with Flyte

When: Saturday, Nov. 4, 8 p.m.

Where: The Orange Peel, 101 Biltmore Ave., theorangepeel.net

Tickets: $25 advance/$28 day of show

(Photo by Citizen Kane Wayne)